Seven Years Strong

Trigger Warning: Medical Imagery, Depression

When I logged into Facebook in the middle of the first week of April, the memories feature brought up a post I hadn’t remembered: I’d written from a hospital bed that I was waiting for my first surgical procedure. The comments were filled with people asking what happened, if I was okay, and my responses were coherent but lacked their usual friendliness (and punctuation).

Seven years ago this week, I was a freshman in college who woke up one morning to find my left leg had swollen by three inches in circumference and was hot to the touch and deep purple. I assumed I’d broken it, hopped to class, and only went to the hospital when my favorite professor spotted me and told me I was so pale she didn’t know how I was standing. I sat in the emergency room for hours because no one thought it was anything serious, only to find myself whisked off on an hour-long ambulance ride after an ultrasound confirmed I had a blood clot that could have killed me quite easily.

I traveled to a larger hospital, had three surgeries, got some metal placed in my leg, and left. For many people, the story would end there with one simple point: I got better.

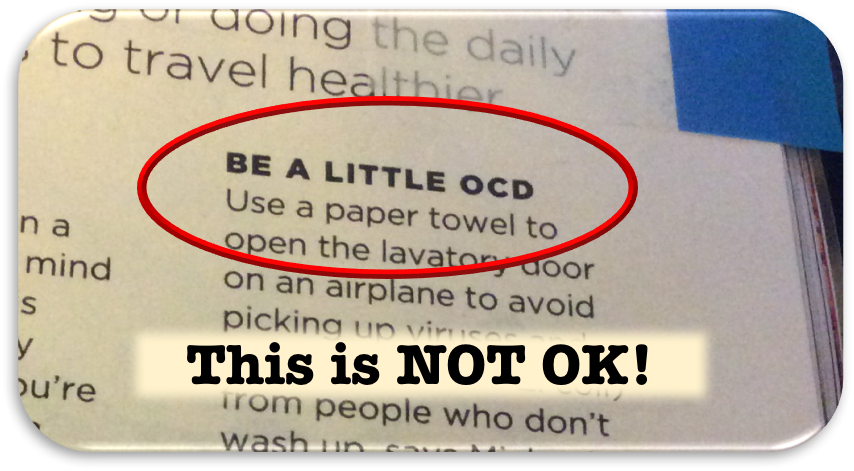

But there were a great many more things that happened during my stay in the hospital that left a more lasting mark, one that wouldn’t show up on any scan. I wasn’t allowed to take my medications that help me bolster myself against the tide of obsessive thoughts that poured in constantly. I was awake for all three surgeries, and felt enough pain from the third that I vividly remember screaming for the doctor to stop until I blacked out. As someone whose OCD has always manifested the most strongly as emetophobia, I coughed up blood.

None of these things were the primary concern of the doctors who were working to save my life. They were on a clock - my left foot had no pulse when I came in - and they had to do what was medically necessary as well as follow their hospital’s policies even as I sank deeper and deeper into the depths of my mind, into places I never wanted to go.

I thought these memories would fade as time went on, like all the normal memories of my life. And for a while, that worked, even as I spent eleven months on a strict regimen of getting my blood drawn daily, my already-restricted diet restricted even more, and my friends not quite understanding why I suddenly wanted to just talk about blood and hospitals.

But two years after my sudden illness, I suddenly found myself plagued by near-constant flashbacks. I was back in that hospital every day, reliving every tiny little detail until I could recite a play-by-play of the entire five days. I jumped at every noise that reminded me of a beeping machine or an ambulance siren. I started having panic attacks over every sensation in my body. My heart raced for days; I stopped sleeping and eating and being able to be by myself. When the days and nights bled into each other, I wished for anything at all to make the pain of constant obsessive thoughts go away. I found myself in a deep depression, on the phone with my psychiatrist more than once a day, trying out a variety of medications and therapeutic techniques to help me get back to myself.

Just like with the OCD, I felt like I was alone. I didn’t know anyone else who had gone through an experience like mine at such a young age, especially when even the doctors were shocked to see how young I was. I didn’t know that, according to a survey conducted in Denmark, young people who live through a blood clot are twice as likely to experience mental health issues afterward (https://www.medicaldaily.com/blood-clot-diagnosis-doubles-risk-mental-health-issues-patients-younger-33-338232). I didn’t know that Clot Connect, the National Blood Clot Alliance, and the Blood Clot Recovery Network all include information specific to emotional health, depression, and flashbacks after the incident due to its suddenness and severity. I didn’t know that, when I felt a spike in anxiety immediately after the blood clot that went away shortly after, I needed to follow up to make sure I really processed everything that happened.

All I knew was that I was, once again, different, and that none of the techniques I’d used throughout my life to help with my OCD were any good against this new threat. I had to start from scratch with barely enough hope to survive at all, and far fewer allies than I expected to help me along the way.

The friends who sent me sympathy cards and gifts when I came out of the hospital turned away when I tried to tell them what was going on in my head. The rabbi who took such good care of me during my recovery was scared of me. To all my friends but one, I was a monster, even though I simply had an illness of the brain rather than the body.

My best friend who stuck by my side, my incredibly supportive family, and my amazing psychiatrist who I first met at the age of nine helped me find a way to survive. I spent what felt like forever working through exposure therapy to get me used to everyday stimuli that reminded me of the hospital and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to help me get my thoughts back on track. It took me a full year to claw myself out of that deep depression and resume my ordinary life, and even now, I mourn for the happiness that was stolen from me in my junior year of college.

Now, seven years after my blood clot, I’m recovered, physically and mentally. There are some parts of me that will never be back to the way they were before, but seeing that Facebook memory this week made me smile instead of shudder.

Know why? I forgot.

I saw the Facebook memory seven years and a day after my ordeal had started, and I hadn’t even thought of it on the actual anniversary of the day everything began. I forgot the anxiety that plagued me for years. I forgot the date and looked at it as just any other day, and once I realized the step I’d taken without even knowing it, I decided to celebrate.

Seven years after I spent a long night awake sobbing in a hospital bed, I found myself in my favorite Chicago restaurant with a new friend I’ve made since moving, trying a new food and also enjoying some wonderful deep dish pizza. We played Pokemon Go, opened packs of cards, and shared plenty of laughs. It was an incredible celebration of the week I’ve dubbed my “healthyversary.”

It can be hard to celebrate this week as a time of health, but I want to make a point of bringing extra joy into my life during the anniversary of the two fiercest fights for my life. I didn’t come out of these experiences believing that everything happens for a reason, and I will never whitewash the pain I had to endure to reach this point in my life. But celebrating the little things, even if it’s as simple as forgetting the date I could have died so many years ago, is a way to celebrate unexpected strength and how far I’ve come out of a terrifying situation. Maybe it’s a sign of even better things to come!

Ellie, a writer new to the Chicago area, was diagnosed with OCD at age 3. She hopes to educate others about her condition and end the stigma against mental illness.