The Real Harm of “Obsessive Christmas Disorder”

Now that December is in full swing, I’ve started seeing one of my least favorite holiday expressions on shirts, memes, and beyond: “Obsessive Christmas Disorder.” Although I know that it’s intended to emphasize how thoughts of and regimented preparations for Christmas take over many people’s minds in December, seeing the phrase still bothers me immensely.

Over the years, friends and family have told me to ignore this. “It’s just a saying - misguided, sure, but what harm can it do?” I am often asked this whenever I express my displeasure at the saying or other expressions about mental illness.

It’s true that, on the surface, reading “Obsessive Christmas Disorder” on a cutesy sweater doesn’t actually hurt me. On the surface, it’s just three words put together in an order that displeases me. But when I think about the mindset it came from and the mindset it encourages, it’s a lot harder to ignore the phrase’s implications.

By using the same acronym as OCD and associating with one typical behavior of people living with OCD - organizing - the phrase draws an association between the pleasurable behavior of preparing for a joyous holiday and the reality of living with OCD as a condition. OCD is far more than the need to organize everything and make sure things are ready to go for December 25. It’s more than thinking a lot about something you’re looking forward to. Thinking of it only in these terms minimizes the lived reality of many people for whom OCD feels like an endless slog, a monster inside, or torture.

The consequence of this is that people don’t take actual mental illnesses seriously when they’re thrown around in phrases like this. If someone hears about a person struggling with OCD after hearing a phrase like “Obsessive Christmas Disorder,” they might think that the person with OCD is just exaggerating, and that it might even be fun, just like the hectic times before Christmas.

These tiny moments can add up, and together, they form the building blocks of the stigma against mental illness. Every “Obsessive Christmas Disorder,” “everyone’s a little [insert mental illness here],” and more contributes to the strange dichotomy where mental illness is either something blown way out of proportion to garner sympathy or legitimately dangerous for society. It takes away the middle ground where people like me live our lives, and reduces people to little more than stereotypes.

I understand that it’s difficult to speak out against something like this. The reality is that, for people who don’t know anyone with OCD, the phrase may seem like nothing more than a slightly distasteful joke. This is what inspires me to share my story, both here and in the autobiographical manuscript I’m working on. More visibility for people living with mental illness - and especially seeing us as human beings with many facets of our lives and personalities beyond the disorder - is key to removing phrases like “Obsessive Christmas Disorder” from the vernacular.

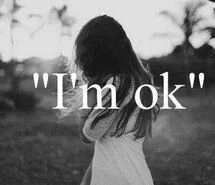

As I write this post, I think of a friend who is currently struggling with his mental health. He struggles a lot with getting help, even from friends and family, because his experiences have been trivialized in ways like this. I write this post for him and for so many people - some of whom I may even know, but not in this context - who feel forced to keep their problems to themselves because an admission of mental illness makes them either a joke or a threat.

“Obsessive Christmas Disorder” might seem innocuous and simple, but it’s not funny. If you see phrases like this about any mental illness, please speak up. It can make a huge difference for 2021 and beyond!

Ellie, a writer new to the Chicago area, was diagnosed with OCD at age 3. She hopes to educate others about her condition and end the stigma against mental illness.